Why a record 13M crypto projects are now dead as Bitcoin critics still claim “anyone can launch a token”

Bitcoin developer, Jameson Lopp, posted a simple observation days after CoinGecko published its 2025 dead coins report.

Ignorant folks claim that Bitcoin isn’t scarce because anyone can launch their own cryptocurrency. They fail to recognize that while anyone can copy code, no one can copy a network of users and infrastructure.

The timing crystallized a tension that’s shaped crypto since the first Bitcoin fork. Token issuance has always been abundant, as spinning up a new coin takes minutes, not months.

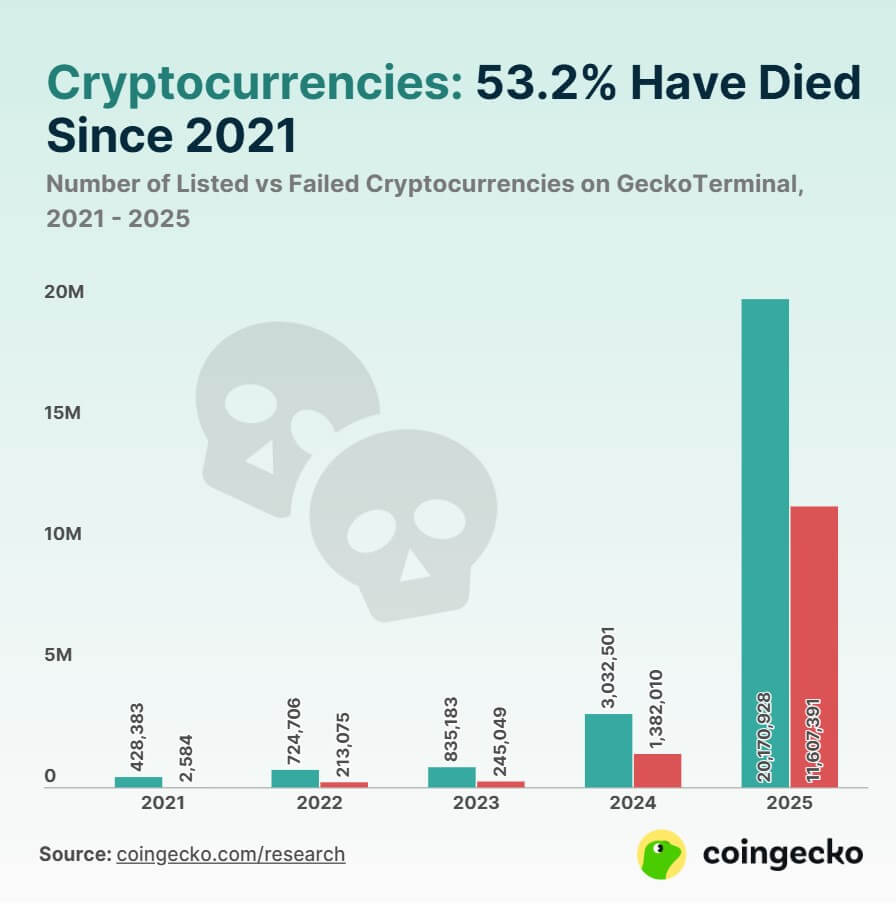

But CoinGecko’s latest dataset turned the “anyone can launch” argument into something measurable: 53.2% of tokens tracked on GeckoTerminal between July 2021 and December 2025 are now inactive, representing roughly 13.4 million failures out of 25.2 million listed.

The year 2025 alone accounted for 11.6 million of those deaths, 86.3% of all failures in the dataset.

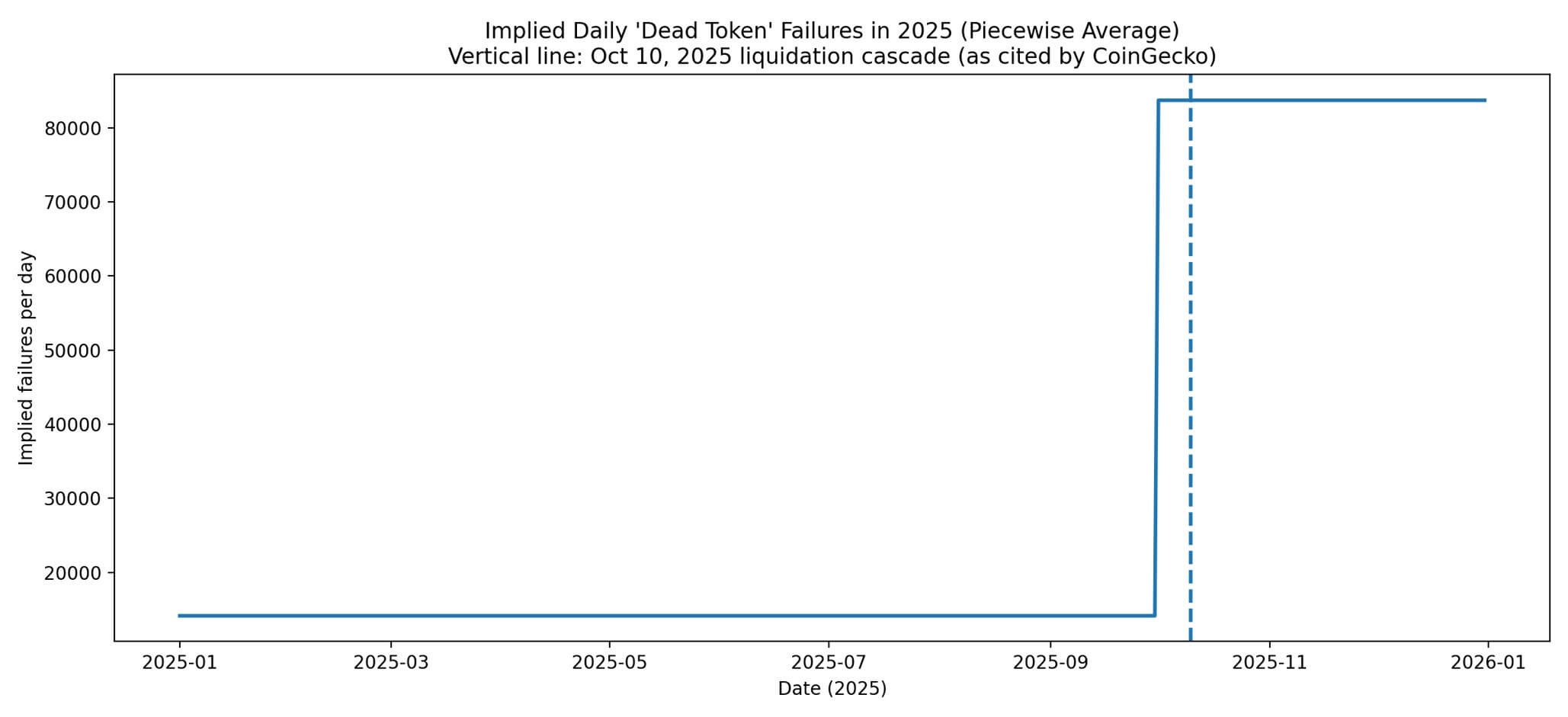

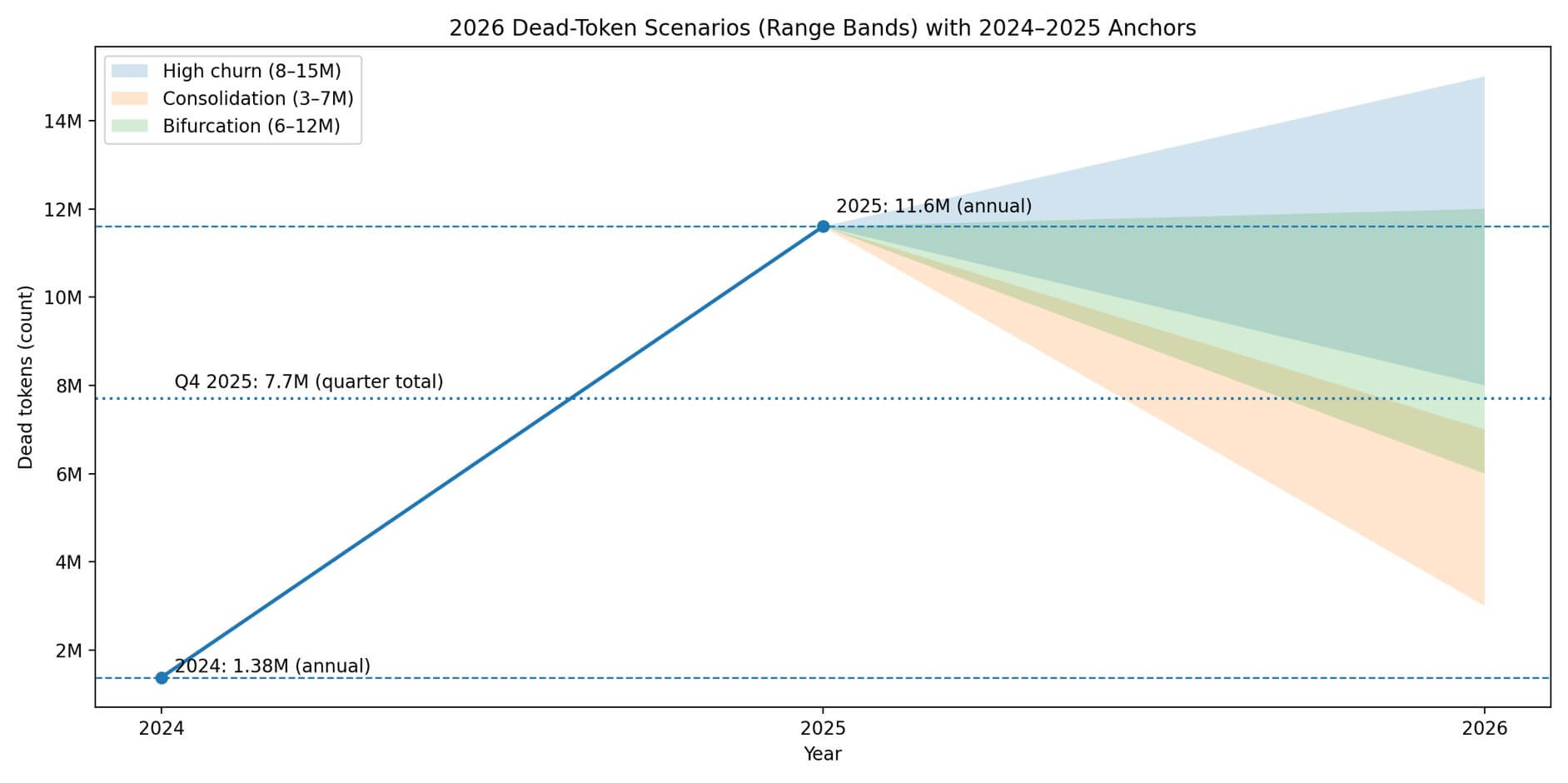

This wasn’t gradual attrition. The fourth quarter of 2025 saw 7.7 million tokens go dark, a pace of roughly 83,700 failures per day. For context, 2024 recorded 1.38 million failures across the entire year.

The acceleration was stark: 2025’s death toll ran 8.4 times higher than 2024’s, compressing what looked like multi-year churn into twelve months. CoinGecko attributes much of the fourth-quarter spike to the Oct. 10 leverage washout, which wiped out $19 billion in leveraged positions, triggering what the firm describes as a historic drawdown.

Total crypto market cap fell 10.4% year-over-year to roughly $3 trillion, with the fourth quarter alone down 23.7%. Bitcoin declined 6.4% while gold surged 62.6%, a divergence that underscored macro risk-off pressure hitting speculative assets hardest.

Scarcity isn’t about the code

Lopp’s framing cuts through a conceptual confusion. Bitcoin’s scarcity doesn’t rest on the difficulty of writing software, but on the difficulty of coordinating humans around a set of rules they collectively choose not to alter.

Forking Bitcoin’s codebase is trivial, while forking the social consensus that gives it credibility as neutral money is not. The dead coins data makes this legible.

Millions of tokens got launched, most piggybacking on low-friction platforms like Pump.fun or launchpad ecosystems that reduced issuance costs to near zero.

GeckoTerminal’s tracked project count exploded from 428,383 in 2021 to over 20.2 million by the end of 2025. Yet the survival rate collapsed.

What CoinGecko measures as “dead” is explicitly tied to trading activity: tokens that once recorded at least one trade but no longer see active exchange. This definition narrows the dataset to tokens that crossed a basic threshold of existence, filtering out purely minted tokens that were never traded.

Even with that filter, the failure rate stayed above 50%. The bottleneck wasn’t launching, but sustaining liquidity and attention long enough for a token to matter.

This maps directly onto what makes Bitcoin’s network scarce.

The asset benefits from a compounding moat: a security budget funded by miners processing over a decade of transactions, a global web of exchanges and custody providers, derivatives markets deep enough to absorb institutional hedging, payment rails integrated into merchant infrastructure, and a developer ecosystem that treats protocol stability as a feature rather than a bug.

Competitors can replicate the code, but they can’t replicate the installed base or the credible commitment not to change the rules opportunistically. Network effects scale nonlinearly, a principle formalized in Metcalfe’s Law-style models that link network value to the square of active participants.

The implication: top networks capture disproportionate value, and most entrants never achieve escape velocity.

When liquidity meets stress

The 2025 die-off wasn’t purely about oversupply.

CoinGecko’s annual market recap shows a system under macro pressure. Stablecoins grew 48.9% to top $311 billion in circulation, adding $102.1 billion even as speculative assets bled. Centralized exchange perpetual volumes hit $86.2 trillion, up 47.4%, while decentralized perpetual volumes reached $6.7 trillion, up 346%.

The infrastructure for settlement and leverage kept scaling, but the breadth of tokens participating in that activity narrowed sharply.

This creates a bifurcated picture. Tokens that served settlement functions or captured genuine trading interest survived, while those relying on hype cycles or thin liquidity got crushed when risk appetite pulled back.

October’s liquidation event acted as a stress test, revealing which projects had real demand and which existed only as placeholders in speculative portfolios.

The fourth-quarter failure rate suggests that most tokens fell into the latter category: assets launched on the assumption that attention and liquidity would follow, but that failed to build distribution or incentive alignment strong enough to weather a drawdown.

CoinGecko’s methodology excludes tokens that never traded and counts only Pump.fun graduates, meaning the actual universe of minted-but-failed tokens is likely larger. The 13.4 million failures represent the subset that reached the point of registering activity before going dormant.

The broader lesson: getting listed is easy, staying relevant is the filter.

What comes next

If 2025 sets a baseline for token mortality under stress, 2026’s trajectory depends on whether issuance patterns shift or whether the same dynamics persist.

Three scenarios map the range.

The first assumes high churn continues. Low-friction launchpads stay dominant, speculative issuance remains cheap, and another liquidity shock produces 8 million to 15 million failures. This path mirrors 2025’s structure, with abundant issuance meeting constrained demand, and treats last year’s extinction event as a repeatable outcome rather than an anomaly.

The second scenario anticipates consolidation. Market participants demand deeper liquidity and longer track records.

Platforms tighten listing standards, traders concentrate in fewer venues, and failure counts drop to 3 million to 7 million as quality filters take hold. This path assumes that 2025’s brutal selection pressure taught the market to price survival risk more accurately, reducing the appetite for tokens without distribution or infrastructure.

The third path combines new issuance with sharper bifurcation. New distribution channels, such as wallet-integrated launches, social trading hooks, and layer-two expansions, drive issuance higher, but only a small subset achieves real network effects.

Failures land in the 6 million to 12 million range, with an even steeper winner-take-most distribution than 2025 produced.

The ranges aren’t predictions, but rather plausible bounds given observed quarterly volatility and the 2024 baseline. The 7.7 million failures in last year’s fourth quarter represent a stress-quarter ceiling, while 2024’s 1.38 million offer a lower bound for non-extreme conditions.

The actual outcome depends on macro conditions, platform incentives, and whether the market internalizes 2025’s lesson or repeats it.

The network can’t be cloned

Lopp’s line about copying code versus copying networks lands harder in light of CoinGecko’s data. Bitcoin’s scarcity isn’t threatened by the existence of millions of alternative tokens; instead, it’s reinforced by the failure rate of those alternatives.

Each dead coin represents an attempt to replicate the network effects, credibility, and infrastructure that took Bitcoin over a decade to build. Most couldn’t sustain trading for a year.

The 2025 data quantifies something crypto participants understood intuitively: issuance is abundant, but survival is scarce. Macro stress accelerated the sorting, but the underlying dynamic predates October’s liquidation cascade.

Tokens that lacked distribution, liquidity depth, or ongoing incentive alignment got filtered out. Meanwhile, the core rails kept scaling, concentrating activity in assets and infrastructure that proved resilient.

Bitcoin’s moat isn’t its codebase. It’s the credible, liquid, infrastructure-rich network that competitors can launch against but can’t copy.

The code is free. The network costs everything.