Microsoft signs $9.7B deal with BTC miner IREN

Microsoft’s $9.7 billion contract with a Texas miner reveals the new math pushing crypto infrastructure toward AI, and what it means for the networks left behind.

IREN’s November 3 announcement collapses two transactions into a single strategic pivot. The first is a five-year, $9.7 billion cloud services contract with Microsoft, while the second is a $5.8 billion equipment deal with Dell to source Nvidia GB300 systems.

The combined $15.5 billion commitment converts roughly 200 megawatts of critical IT capacity at IREN’s Childress, Texas campus from potential Bitcoin mining infrastructure into contracted GPU hosting for Microsoft’s AI workloads.

Microsoft included a 20% prepayment, roughly $1.9 billion upfront, signaling urgency around a capacity constraint the company’s CFO flagged as extending at least through mid-2026.

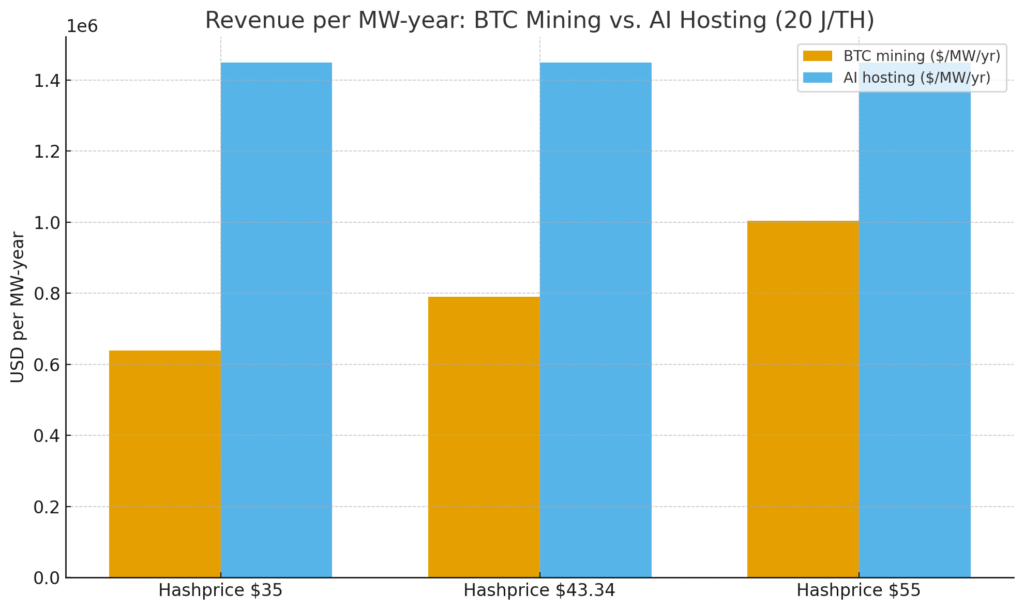

The deal’s structure makes explicit what miners have been calculating quietly. At the current forward hash price, every megawatt dedicated to AI hosting generates roughly $500,000 to $600,000 more in annual gross revenue than the same megawatt hashing Bitcoin.

That margin, an approximately 80% uplift, creates the economic logic driving the most significant infrastructure reallocation in crypto’s history.

The revenue math that broke

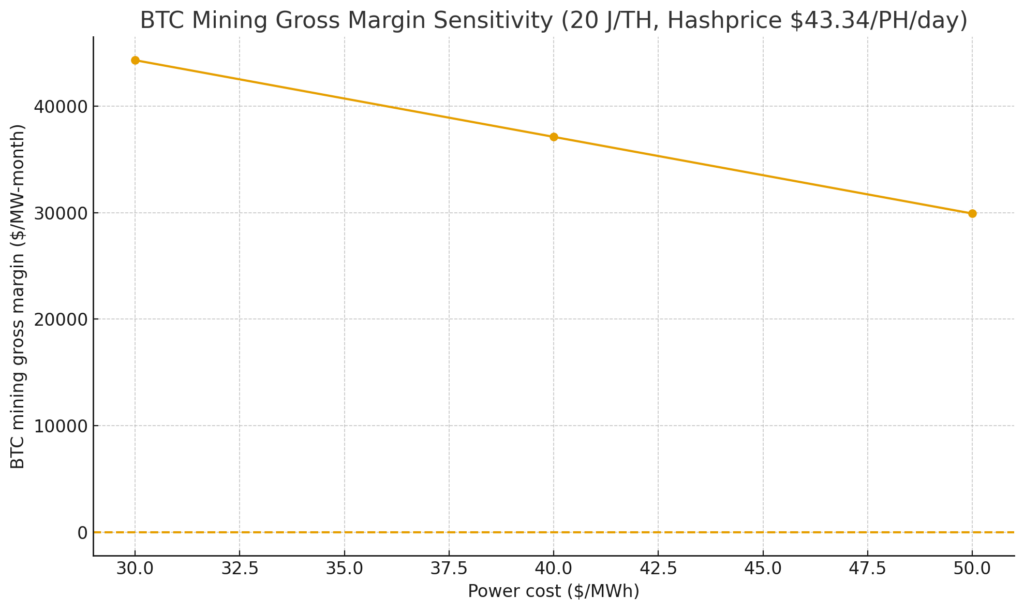

Bitcoin mining at 20 joules per terahash efficiency generates approximately $0.79 million per megawatt-hour when the hash price is $43.34 per petahash per day.

Even at $55 per petahash, which requires either sustained Bitcoin price appreciation or fee-spike activity, mining revenue climbs only to $1.00 million per megawatt-year.

AI hosting, by contrast, benchmarks around $1.45 million per megawatt-year based on Core Scientific’s disclosed contracts with CoreWeave. This equates to $8.7 billion in cumulative revenue across approximately 500 megawatts over a 12-year period.

The crossover point where Bitcoin mining matches AI hosting economics sits between $60 and $70 per petahash per day for a 20 joule-per-terahash fleet.

For the bulk of the mining industry, which runs 20-to-25 joule equipment, the hash price would need to rise 40% to 60% from current levels to make Bitcoin mining as lucrative as contracted GPU hosting.

That scenario requires either a sharp Bitcoin price rally, sustained fee pressure, or a meaningful drop in network hashrate, none of which operators can bank on when Microsoft offers guaranteed, dollar-denominated revenue starting immediately.

Why Texas won the bid

IREN’s Childress campus is situated on ERCOT’s grid, where wholesale power prices averaged $27 to $34 per megawatt-hour in 2025.

These numbers are lower than the US national average of nearly $40 and significantly cheaper than those in PJM or other eastern grids, where data center demand drove capacity auction prices to regulatory caps.

Texas benefits from rapid solar and wind expansion, keeping baseline power costs competitive. But ERCOT’s volatility creates additional revenue streams that amplify the economic case for flexible compute infrastructure.

Riot Platforms demonstrated this dynamic in August 2023 when it collected $31.7 million in demand response and curtailment credits by shutting down mining operations during peak pricing events.

The same flexibility applies to AI hosting if contract structures are structured as a pass-through: operators can curtail operations during extreme pricing events, collect ancillary service payments, and resume operations when prices normalize.

PJM’s capacity market tells the other side of the story. Data center demand pushed capacity prices to administrative caps for forward delivery years, signaling constrained supply and multi-year queues for interconnection.

ERCOT operates an energy-only market with no capacity construct, meaning interconnection timelines compress and operators face fewer regulatory hurdles.

IREN’s 750-megawatt campus already has the power infrastructure in place; converting from mining to AI hosting requires swapping ASICs for GPUs and upgrading cooling systems rather than securing new transmission capacity.

The deployment timeline and what happens to miners

Data Center Dynamics flagged IREN’s “Horizon 1” module in the second half of 2025: a 75-megawatt, direct-to-chip liquid-cooled installation designed for Blackwell-class GPUs.

Reports confirmed that the phased deployment will extend through 2026, scaling to approximately 200 megawatts of critical IT load.

That timeline aligns precisely with Microsoft’s mid-2026 capacity crunch, making third-party capacity immediately valuable even if hyperscale buildouts eventually catch up.

The 20% prepayment functions as schedule insurance. Microsoft locks delivery milestones and shares some of the supply-chain risk inherent in sourcing Nvidia’s GB300 systems, which remain supply-constrained.

The prepayment structure suggests Microsoft values certainty over waiting for potentially cheaper capacity in 2027 or 2028.

If IREN’s 200 megawatts represents the leading edge of a broader reallocation, network hashrate growth moderates as capacity exits Bitcoin mining. The network recently surpassed one zettahash per second, reflecting steady increases in difficulty.

Removing even 500 to 1,000 megawatts from the global mining base, a plausible scenario if Core Scientific’s 500 megawatts combines with IREN’s pivot and similar moves from other miners, would slow hashrate growth and provide marginal relief on hash price for remaining operators.

Difficulty adjusts every 2,016 blocks based on actual hashrate. If aggregate network capacity declines or stops growing as quickly, each remaining petahash earns slightly more Bitcoin.

High-efficiency fleets with hash rates below 20 joules per terahash benefit most because their cost structures can sustain lower hash rate levels than older hardware.

Treasury pressure eases for miners that successfully pivot capacity to multi-year, dollar-denominated hosting contracts.

Bitcoin mining revenue fluctuates with price, difficulty, and fee activity; operators with thin balance sheets often face forced selling during downturns to cover fixed costs.

Core Scientific’s 12-year contracts with CoreWeave de-link cash flow from Bitcoin’s spot market, converting volatile revenue into predictable service fees.

IREN’s Microsoft contract achieves the same outcome: financial performance depends on uptime and operational efficiency rather than whether Bitcoin trades at $60,000 or $30,000.

This de-linking has second-order effects on Bitcoin’s spot market. Miners represent a structural source of sell pressure because they must convert some mined coins to fiat to cover electricity and debt service.

Reducing the mining base removes that incremental selling, marginally tightening Bitcoin’s supply-demand balance. If the trend scales to multiple gigawatts over the next 18 months, the cumulative impact on miner-driven selling becomes material.

The risk scenario that reverses the trade

Hash price doesn’t remain static. If Bitcoin’s price rallies sharply while the network’s hashrate growth moderates due to capacity reallocation, the hashprice could climb above $60 per petahash per day and approach levels where mining rivals AI hosting economics.

Add a fee spike from network congestion, and the revenue gap narrows further. Miners who locked capacity into multi-year hosting contracts can’t easily pivot back, since they’ve committed to hardware procurement budgets, site designs, and customer SLAs around GPU infrastructure.

Supply-chain risk sits on the other side. Nvidia’s GB300 systems remain constrained, liquid-cooling components face lead times measured in quarters, and substation work can delay site readiness.

If IREN’s Childress deployment slips beyond mid-2026, the revenue guarantee from Microsoft loses some of its immediate value.

Microsoft needs capacity when its internal constraints bite hardest, not six months later when the company’s own buildouts come online.

Contract structure introduces another variable. The $1.45 million per megawatt-year figure represents service revenue, and margins depend on SLA performance, availability guarantees, and whether power costs pass through cleanly.

Some hosting contracts include take-or-pay power commitments that protect the operator from curtailment losses but cap upside from ancillary services.

Others leave the operator vulnerable to ERCOT’s price fluctuations, creating margin risk if extreme weather drives power costs above pass-through thresholds.

What Microsoft actually bought

IREN and Core Scientific aren’t outliers, but rather the visible edge of a re-optimization playing out across the publicly traded mining sector.

Miners with access to cheap power, ERCOT or similar flexible grids, and existing infrastructure can pitch hyperscalers on capacity that’s faster and cheaper to activate than greenfield data center construction.

The limiting factors are cooling capacity, direct-to-chip liquid cooling requires different infrastructure than air-cooled ASICs, and the ability to secure GPU supply.

What Microsoft bought from IREN wasn’t just 200 megawatts of GPU capacity. It bought delivery certainty during a constraint window when every competitor faces the same bottlenecks.

The prepayment and five-year term signal that hyperscalers value speed and reliability enough to pay premiums over what future capacity might cost.

For miners, this premium represents an arbitrage opportunity: redeploy megawatts toward the higher-revenue use case while the hash price remains suppressed, then reassess when Bitcoin’s next bull cycle or fee environment changes the math.

The trade works until it doesn’t, and the timing of that reversal will determine which operators captured the best years of AI infrastructure scarcity and which ones locked in just before mining economics recovered.