Sam Bankman-Fried requests new trial claiming FTX had $16.5 billion surplus in 2022, but does it matter?

Sam Bankman-Fried filed a motion for a new trial on Feb. 10, advancing a claim that reframes FTX’s collapse not as fraud-driven insolvency but as a recoverable liquidity crisis.

The motion invokes Rule 33 of the Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure, which permits courts to grant new trials when “the interest of justice so requires,” typically when newly discovered evidence surfaces or fundamental trial errors taint the verdict.

SBF’s filing argues both that testimony from silenced witnesses would have refuted the government’s insolvency narrative and that prosecutorial intimidation denied him due process.

At the motion’s center sits a striking numerical claim: FTX held a positive net asset value of $16.5 billion as of the November 2022 bankruptcy petition date.

The implication is that if the estate can eventually repay customers, the trial’s portrayal of billions in stolen, irrecoverable funds was misleading. According to Reuters, the bankruptcy plan contemplates distributing at least 118% of customers’ November 2022 account values.

However, this accounting argument collides with a deeper question: Does repayment erase fraud?

The answer illuminates why “solvency” in crypto exchanges operates across dimensions that balance sheets alone cannot capture, and why FTX has become a case study in how narratives are constructed when courtroom facts and financial reality diverge.

Whole in dollars, not in kind

Bankruptcy law fixes claims at a snapshot. Under 11 U.S.C. § 502(b), the value of creditor claims is determined as of the petition date. In this case, Nov. 11, 2022.

For FTX customers, that means their entitlements were calculated using crypto prices from the depths of the 2022 market collapse, not the subsequent rally that saw Bitcoin climb from under $17,000 to a peak of $126,000.

Court filings in the Bahamas proceedings make this explicit: claims for appreciation after the petition date are not part of the core customer entitlement. When the estate announced distributions exceeding 100%, that percentage reflects petition-date dollar values, not the in-kind restoration of the specific tokens customers believed they held.

A customer who deposited one Bitcoin in 2021 does not receive one Bitcoin back. Instead, they receive the November 2022 dollar-equivalent value of the Bitcoin, plus a premium reflecting asset recoveries.

Customers objected precisely because the petition-date valuation mechanism excluded them from the crypto market’s subsequent appreciation. Being paid “in full” under the bankruptcy doctrine can still mean being underpaid relative to the asset you thought you owned.

The legal framework treats crypto balances as dollar-denominated claims, even when users experience them as specific-asset holdings with 24/7 withdrawal rights.

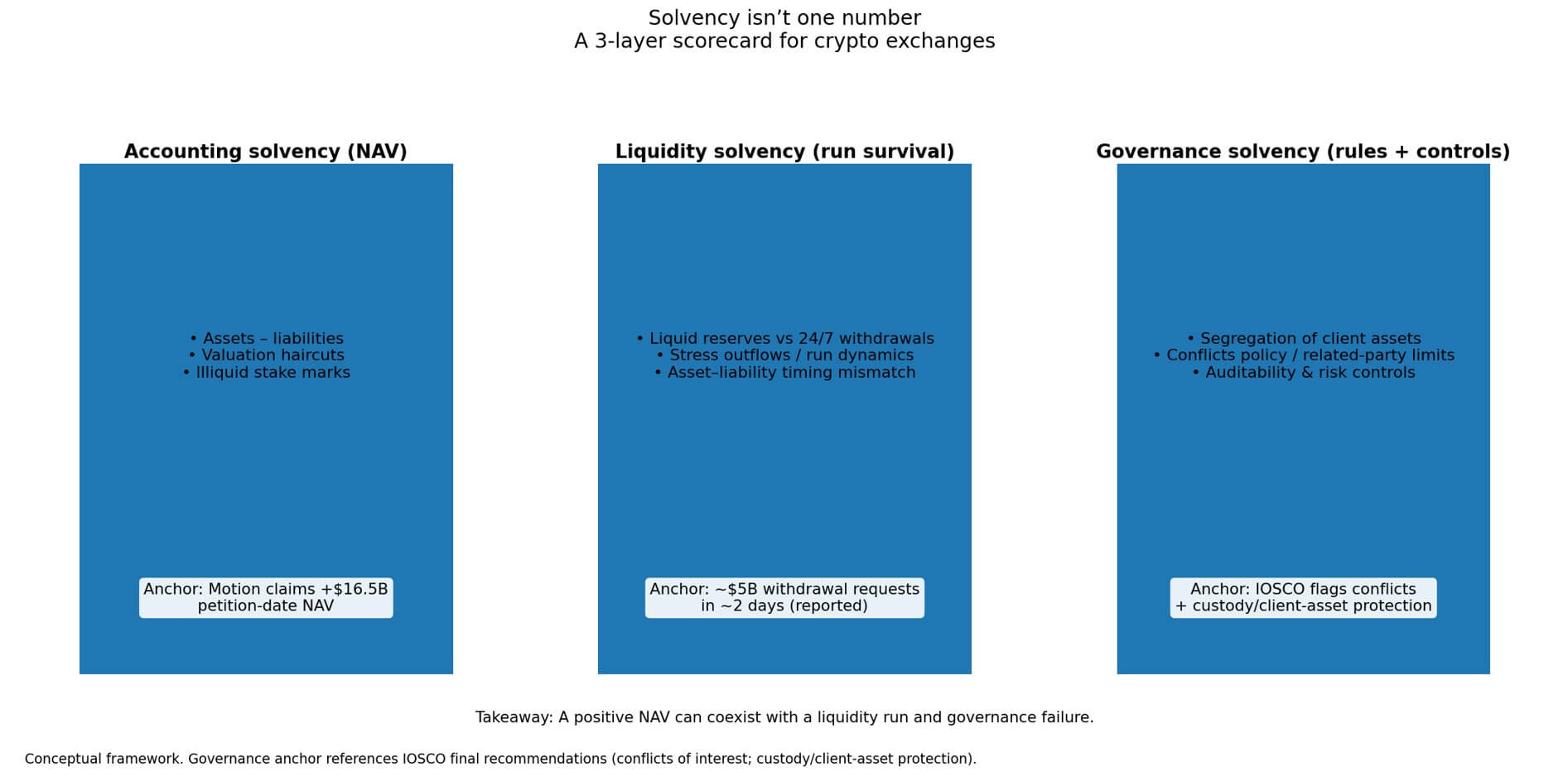

Three layers of solvency (and why NAV isn’t enough)

FTX’s motion treats solvency as a single accounting question: do assets exceed liabilities at a point in time?

However, crypto exchanges face a more complex solvency architecture that operates across three dimensions.

Accounting solvency, defined by net asset value, is the balance sheet view that the motion emphasizes. Even if the $16.5 billion figure is accurate, it depends entirely on valuation choices: which assets counted, at what haircuts, and how liabilities were defined.

The estate’s recoveries benefited from venture capital stakes in companies like Anthropic that weren’t immediately liquid in November 2022 but later returned substantial value.

Liquidity solvency concerns whether crypto exchanges are structurally sound. Liabilities are on-demand, typically denominated in specific tokens, and confidence-sensitive.

Academic work analyzing the 2022 “crypto winter” explicitly frames the period as a run-driven crisis. When FTX faced its liquidity crisis in November 2022, it processed roughly $5 billion in withdrawal requests over two days.

The question wasn’t whether the venture portfolio would eventually be worth something, but whether liquid, on-chain assets matched on-demand liabilities in real time.

Governance solvency is where fraud enters, irrespective of recovery.

Did the exchange represent that customer assets were segregated? Were conflicts of interest controlled? These questions persist even if the estate later recovers enough to pay claims.

The IOSCO final recommendations on crypto-asset regulation treat conflicts of interest and custody/client-asset protection as central failure modes, distinct from simple insolvency.

Why repayment doesn’t dissolve fraud

Trial testimony established that Alameda Research, Bankman-Fried’s trading firm, ran what prosecutors described as a multi-billion-dollar deficit in its FTX user account, using customer deposits as collateral and operating capital.

The government’s case rested on misrepresentation, comprising customers being told that assets were segregated, misuse of funds, with funds commingled and lent to Alameda, and governance failure characterized by risk controls being bypassed or nonexistent.

The motion argues that if customers can be repaid, the “billions in losses” narrative was false. But fraud law and bankruptcy law ask different questions.

Fraud focuses on what was represented at the time and what was done with customer property. Bankruptcy focuses on what creditors ultimately recover.

Even under the motion’s own framing, the Debtors’ estate initially claimed both FTX and FTX US were insolvent on Nov. 11, 2022, then revised that view only after extensive asset recovery work.

Solvency assessments depend on assumptions, and those assumptions change as illiquid assets get valued, disputes get resolved, and market conditions shift.

| Question | Bankruptcy/balance-sheet lens | Criminal/fraud lens | What evidence answers it | What it does not prove |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Were customers “made whole”? | Measured in petition-date USD claims; distributions can exceed 100% of Nov 2022 values | Not the standard; repayment doesn’t determine criminal liability | Plan terms + distribution notices; court orders applying petition-date valuation; reporting on “≥118% of Nov 2022 account values” | That customers got their coins back, or that wrongdoing didn’t occur |

| Were customers made whole in-kind? | Generally no: entitlement is dollar value at petition date, not token restitution | Still irrelevant to intent/misrepresentation; in-kind shortfall may show reliance on representations | Bankruptcy valuation rulings; customer objections re: lost upside | That in-kind loss alone proves fraud (it may also reflect bankruptcy doctrine) |

| Was there a liquidity mismatch during the run? | Liquidity crunch can exist even if NAV later turns positive; runnable liabilities vs illiquid assets | Can support theories of reckless risk-taking, concealment, or misuse depending on conduct | Withdrawal demand figures; internal liquidity dashboards; contemporaneous comms; timing of pauses/halts | That “it was only a run” excuses misuse of customer property |

| Were customer assets segregated as represented? | Core governance/custody issue; segregation determines how claims and recoveries should work | Central to fraud: what was promised vs what was done with customer property | TOS/marketing statements; custody policies; ledger traces; internal controls docs | That later distributions validate earlier custody practices |

| Were conflicts controlled (exchange vs affiliated trading)? | Conflict structure affects risk, valuation haircuts, recoveries, and creditor outcomes | Conflicts can be evidence of intent, concealment, or self-dealing | Org charts; related-party agreements; permissions/allowlists; governance minutes | That conflicts = crime by themselves (but unmanaged conflicts raise the risk) |

| Did governance/risk controls prevent misuse? | Weak controls raise probability of loss/run; affects creditor recoveries and supervisory findings | Weak controls can support negligence/recklessness; bypassing controls can support intent | Audit trails; risk-limit systems; exception logs; approval workflows; whistleblower/internal reports | That “controls existed on paper” means they functioned in practice |

| Did later recoveries change the ex ante conduct? | Recoveries can change the estate’s solvency story and payout math over time | Generally no: fraud evaluates conduct and intent at the time | Timeline of asset discovery/valuation revisions; litigation recoveries; VC stake monetizations | That ex post solvency retroactively makes earlier statements true |

| Does positive NAV negate misrepresentation? | Positive NAV may depend on valuation choices (haircuts, illiquid marks, disputed assets) and says nothing about liquidity | No: misrepresentation can exist even if a firm could theoretically pay back later | Basis for NAV claim; asset/liability definitions; valuation memos; trial record on representations | That “NAV positive” means “no fraud,” or that customers faced no real-time withdrawal risk |

What this means going forward

If the motion’s $16.5 billion NAV claim becomes the new reference point, it shifts the FTX narrative from “massive hole” to “liquidity mismatch with eventual recovery.”

That shift has consequences beyond Bankman-Fried’s appeal.

First, it demonstrates that proof-of-reserves without corresponding liability disclosures and liquidity stress testing is incomplete. Showing that assets exist doesn’t prove that those assets can meet withdrawal demand when confidence breaks.

The next crypto crisis won’t announce itself as insolvency. It will appear as opacity plus a run-on mismatched liquidity.

Second, it signals that regulation will converge on governance chokepoints: segregation requirements, conflict-of-interest controls, and real-time liability transparency.

The vertically integrated model, where the same entity operates the exchange, holds custody, runs a trading desk, and manages a venture fund, becomes the structural target, not just individual misconduct.

Third, the petition-date valuation doctrine becomes a market-structure question. If bankruptcy law systematically shifts post-petition appreciation away from customers and into the estate, users internalize the risk of custody differently.

That dynamic may accelerate the transition to self-custody and decentralized infrastructure in future cycles.

The courtroom-versus-ledger problem

The motion ultimately asks: if customers end up financially whole under the bankruptcy plan, how can the trial’s fraud narrative stand?

The answer lies in the distinction between ex post recovery and ex ante conduct. Fraud isn’t erased by later solvency, any more than a bank robbery is undone if the money is eventually returned.

FTX’s balance sheet and FTX’s courtroom record tell different stories because they measure different things.

The ledger asks whether the value was preserved. The trial asked whether the rules were followed, the representations were honest, and the risks were disclosed.

The fact that the estate recovered enough assets to pay claims at petition-date values does not resolve whether customer funds were misused, whether governance failed, or whether users were misled about the safety of their deposits.

The FTX case will be remembered not for its final recovery percentage but for exposing the gap between crypto solvency as a spreadsheet exercise and crypto solvency as a real-time, multi-dimensional governance question.

“Made whole” in bankruptcy terms can coexist with “defrauded” in criminal-law terms. The motion’s $16.5 billion NAV claim doesn’t dissolve that tension. It makes it explicit.