Are You a Freelancer? North Korean Spies May Be Using You

North Korea’s IT operatives are shifting strategies and recruiting freelancers to provide proxy identities for remote jobs.

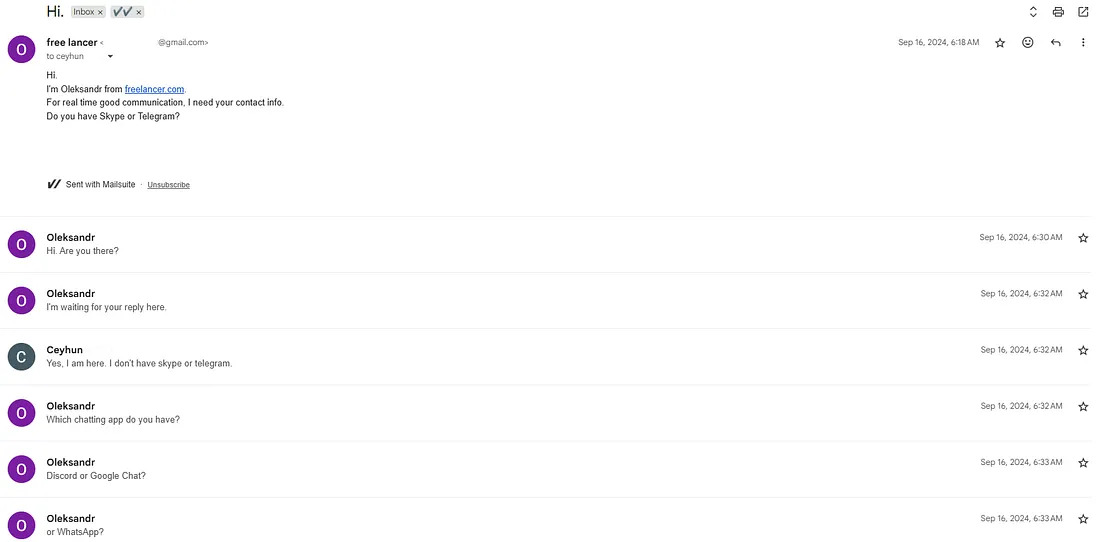

Operatives are contacting job seekers on Upwork, Freelancer and GitHub before moving conversations to Telegram or Discord, where they coach them through setting up remote access software and passing identity verifications.

In earlier cases, North Korean workers scored remote gigs using fabricated IDs. According to Heiner García, a cyber threat intelligence expert at Telefónica and a blockchain security researcher, operatives are now avoiding those barriers by working through verified users who hand over remote access to their computers.

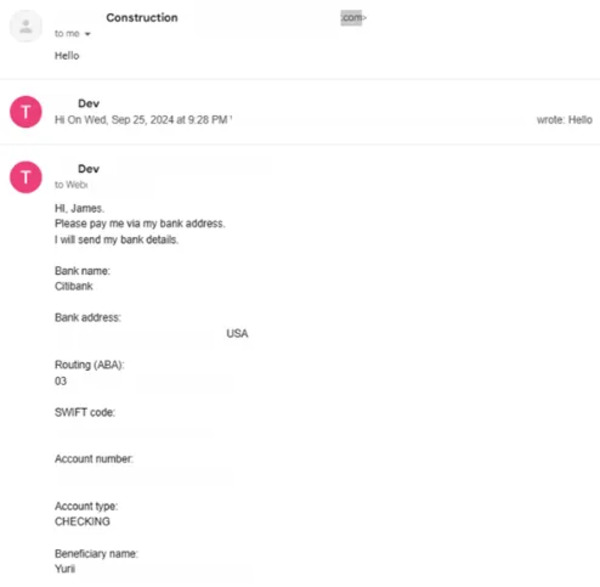

The real owners of the identities receive only a fifth of the pay, while the rest of the funds are redirected to the operatives through cryptocurrencies or even traditional bank accounts. By relying on real identities and local internet connections, the operatives can bypass systems designed to flag high-risk geographies and VPNs.

Inside the evolving recruitment playbook of North Korean IT workers

Earlier this year, García set up a dummy crypto company and, together with Cointelegraph, interviewed a suspected North Korean operative seeking a remote tech role. The candidate claimed to be Japanese, then abruptly ended the call when asked to introduce himself in Japanese.

García continued the conversation in private messages. The suspected operative asked him to buy a computer and provide remote access.

The request aligned with patterns García would later encounter. Evidence linked to suspicious profiles included onboarding presentations, recruitment scripts and identity documents “reused again and again.”

Related: North Korean spy slips up, reveals ties in fake job interview

García told Cointelegraph:

They install AnyDesk or Chrome Remote Desktop and work from the victim’s machine so the platform sees a domestic IP.”

The people handing over their computers “are victims,” he added. “They are not aware. They think they are joining a normal subcontracting arrangement.”

According to chat logs he reviewed, recruits ask basic questions such as “How will we make money?” and perform no technical work themselves. They verify accounts, install remote-access software and keep the device online while operatives apply for jobs, speak to clients and deliver work under their identities.

Though most appear to be “victims” unaware of who they’re interacting with, some appear to know exactly what they are doing.

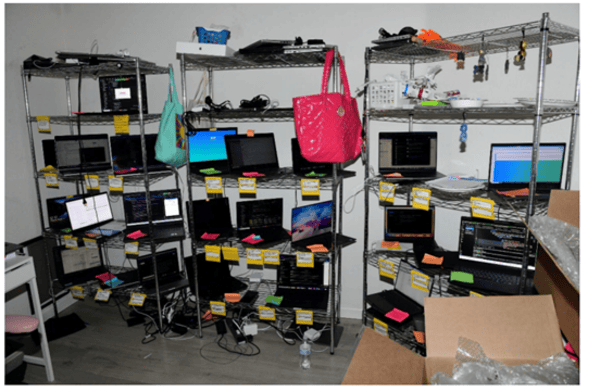

In August 2024, the US Department of Justice arrested Matthew Isaac Knoot of Nashville for running a “laptop farm” that allowed North Korean IT workers to appear as US-based employees using stolen identities.

More recently in Arizona, Christina Marie Chapman was sentenced to more than eight years in prison for hosting a similar operation that funneled more than $17 million to North Korea.

A recruitment model built around vulnerability

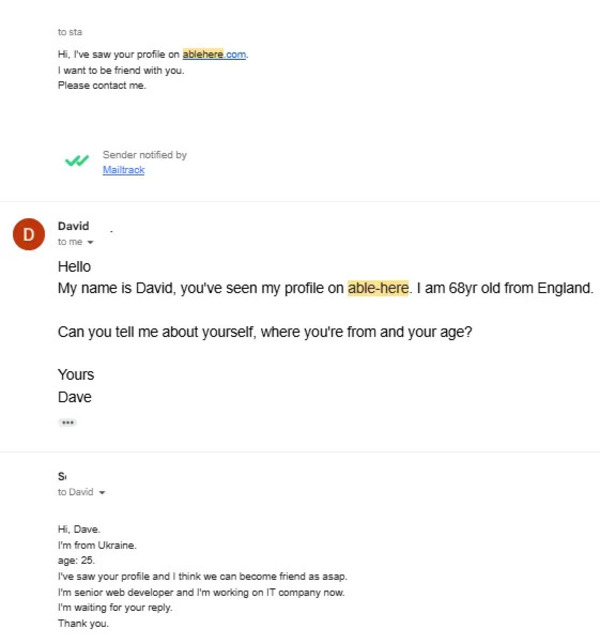

The most prized recruits are in the US, Europe and some parts of Asia, where verified accounts provide access to high-value corporate jobs and fewer geographic restrictions. But García also observed documents belonging to individuals from regions with economic instability, such as Ukraine and Southeast Asia.

“They target low-income people. They target vulnerable people,” García said. “I even saw them trying to reach people with disabilities.”

North Korea has spent years infiltrating the tech and crypto industries to generate revenue and gain corporate footholds abroad. The United Nations said DPRK IT work and crypto theft are allegedly funding the country’s missile and weapons programs.

Related: From Sony to Bybit: How Lazarus Group became crypto’s supervillain

García said the tactic goes beyond crypto. In one case he reviewed, a DPRK worker used a stolen US identity to present themselves as an architect from Illinois, bidding on construction-related projects on Upwork. Their client received completed drafting work.

Despite the focus on crypto-related laundering, García’s research found that traditional financial channels are also being abused. The same identity-proxy model allows illicit actors to receive bank payments under legitimate names.

“It’s not only crypto,” García said. “They do everything — architecture, design, customer support, whatever they can access.”

Why platforms still struggle to spot who’s really working

Even as hiring teams grow more alert to the risk of North Korean operatives securing remote roles, detection typically arrives only after unusual behavior triggers red flags. When an account is compromised, the actors pivot to a new identity and keep working.

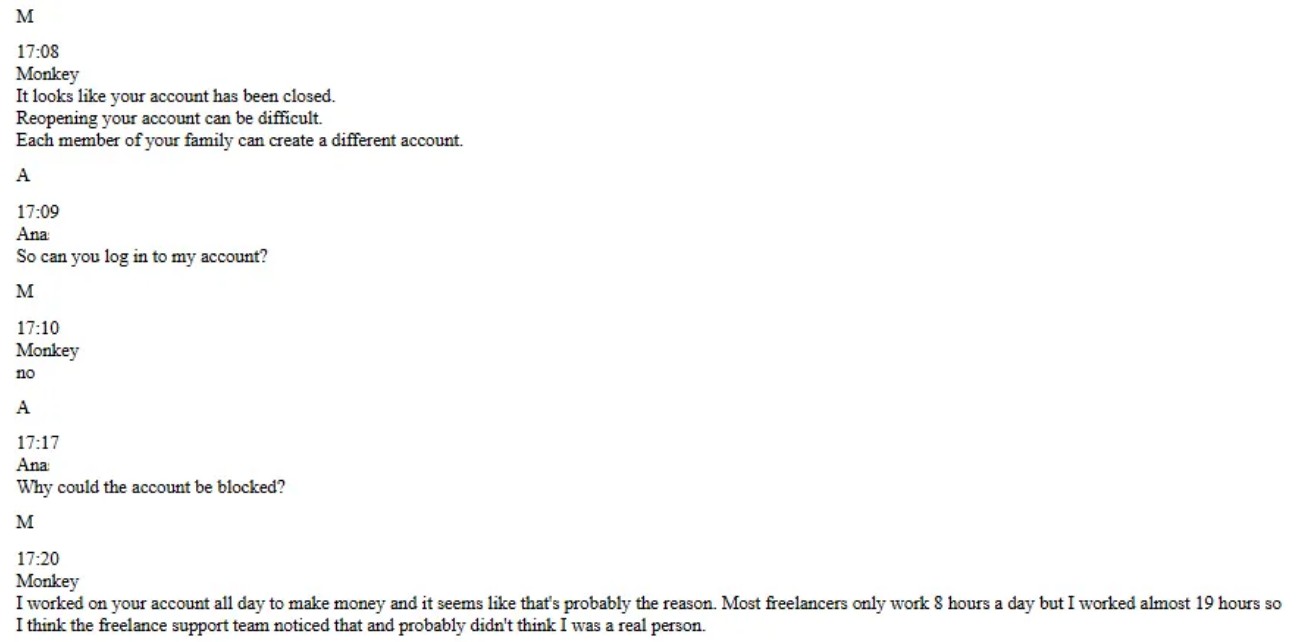

In one case, after an Upwork profile was suspended for excessive activity, the operative instructed the recruit to ask a family member to open the next account, according to chat logs reviewed.

This churn of identities makes both accountability and attribution difficult. The person whose name and paperwork are on the account is often deceived, while the individual actually doing the work is operating from another country and is never directly visible to freelancing platforms or clients.

The strength of this model is that everything a compliance system can see looks legitimate. The identity is real, and the internet connection is local. On paper, the worker meets every requirement, but the person behind the keyboard is someone entirely different.

García said the clearest red flag is any request to install remote-access tools or let someone “work” from your verified account. A legitimate hiring process doesn’t need control of your device or identity.

Magazine: Bitcoin OG Kyle Chassé is one strike away from a YouTube permaban